|

| Bunker Hill by Don Troiani (artist's website) |

The American Army of 1775 had been a gathering of militia companies, begun by Massachusetts and coming to include contingents from all the New England provinces. This was refined and polished into a regular army of sorts by a cadre of political-military leaders, many of them veterans of the late war with France and Spain or self-taught students of the military arts. The new Continental government adopted this army and in 1776 began expanding it, gradually turning what were at first a collection of separate, Provincial forces into a Continental Army. The following year of war tested the army's officers and men; the fire of combat began melting away the dross of cowards and incompetents (though many brave and bold men were also lost in that year of successive disasters for the Continental Army).

But though by the end of 1776, the men of the Continental Army were becoming veterans, they were also disappearing. Since the army had been raised, like previous Provincial forces, to address a short-term emergency, the army of 1776 melted away as enlistments expired and privations increased. For 1777, a new army would have to be recruited, an army that would serve for the duration of the war. Congress would need to work more closely with the commanders of its army and their staffs, so as to ensure that they built together a stronger, more professional, better trained and equipped, more durable and effective army.

After the defeats of the New York campaign in 1776, General George Washington had taken his army across the Jerseys and across the barrier of the broad Delaware River to temporary safety in Pennsylvania. To increase the value of this barrier, he had gathered up or destroyed as many boats as possible along the navigable course of the river, so as to prevent the British from pursuing him across it. After the winter campaign of 1776/1777 in which he defeated the Crown Forces at Trenton and Princeton, he changed plans and withdrew into the Watchung Mountains of New Jersey instead of back across the Delaware. The mountains provided almost as much protection as the river from a swift British approach, and he could move down out of them more easily and quickly than he could cross the river.

Reforging the Blade

|

| Continental Army encampment at Morristown (warfarehistorynetwork.com) |

that made up the bulk of the army was perhaps the largest task, the artillery, cavalry, staff, and logistical elements of the army also received considerable attention and, as far as possible, upgrades. Congress authorized the creation or transfer of cavalry units from the provinces to create the army's first four regiments of light dragoons, troops that Washington saw more valuable as reconnaissance and intelligence assets than as battlefield troops. Artillery units were likewise reorganized and transferred from the control of the colonies' service to that of Congress. Guns were given new, lighter carriages to increase the speed with which they could move to support the infantry. The army was reorganized into divisions and brigades, each with their own commanding officers, infantry regiments, and artillery brigades, which made supplying, planning, and commanding the army in battle easier. Washington overhauled his staff, finding replacements for the young men of his "family" who had been promoted to command some of the new regiments that Congress was putting into the field. And new logistical and support organizations ensured that arms were manufactured and procured more systematically and that uniforms and comestibles were better accounted for and supplied to the army.

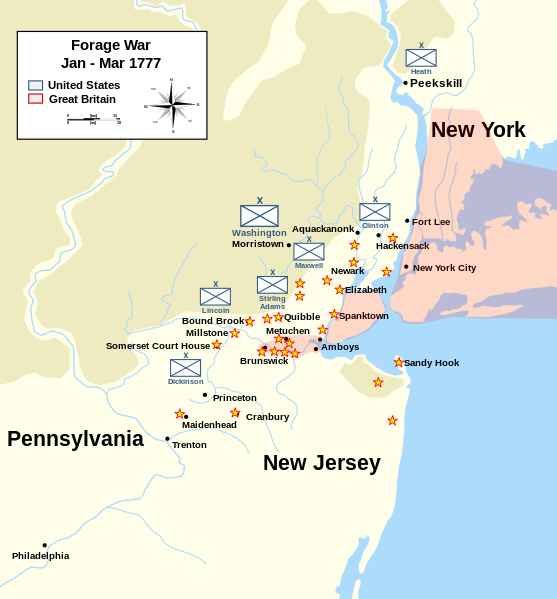

But while this new army was being assembled, Washington relied heavily on what he felt to be a rather weak or broken reed--the state militias. The New Jersey militia had become very animated by the damage done by British and Hessian troops over the autumn and winter, and the combats between militia units and occupying troops looking for supplies became known as the Forage War. Normally such engagements would be quite limited in scope, but as the ferocity of encounters grew and desire on both sides to draw the enemy into a grave trap increased, so did the size of battles. In the fight at Spanktown in February 1777, nearly an entire division was engaged on both sides.

|

| Engagements of the Forage War (Wikimedia) |

Washington had been explicit in his discussions with his own staff and with Congress about his desire to avoid an open field battle with the British army, at least while his forces were smaller, less experienced, and less well supported than their opponents. He knew the value of fighting from fixed positions, but he also knew that the British would do their best to maneuver in such a way as to force him out of any works he should build, if they could possibly do so. Moreover, if he simply immured his command in a fortress, it would be unable to protect the countryside around it and risk a siege in which he might lose the entire army and its supplies at once. So he wanted to keep tabs on what the British were doing, so he would have plenty of time to react.

In any war, keeping tabs on the enemy is part of the art and craft of reconnaissance. You want to know where the enemy is, what his numbers and equipment are, what he's doing, and if he shows any sign of moving, and if so where he may be going. (Reconnaissance also covers things like knowing the lay of the land, both around your current position and anywhere you or your enemy might want to move, what the state of local population is, where you may be able to find more supplies, and things of that sort.) And ideally one finds those things out very close to the enemy, so you have time to react to any changes, rather than close to your position, where you may not have time to use the information you find.

The enemy, of course, would like the same information about your forces, the local population, and the local terrain. And both of you want to prevent the other from gaining all of this useful knowledge. So between two armies there will be a mass of scouts, spies, counter-scouts, guards, patrols, and outposts.

Of course, the 18th century being what it was, there was no real staff college to learn this sort of thing, but numerous helpful military gentlemen had published manuals on how this sort of thing was done. Several of these guides were to be found in Washington's personal camp library. (PDF) Another would be written by one of the Revolution's leading practitioners of Partisan Warfare.

In its essence, the idea was to have a series of posts, or "guards," between your lines and your enemy's. These would send out patrols to gain information and other patrols to prevent his scouts from getting any information. Each guard would be small, and behind several of them, closer to your army, you would have a smaller number of larger posts or "grand guards" ready to reinforce any guard that might be attacked, to supply troops to relieve those that had been on guard duty for a long time, and occasionally to mount small attacks on the enemy's guards and grand guards so as to disrupt their operations, do some minor damage, and generally be a nuisance. The attack at Bound Brook in April 1777 was just one of these.

This sort of skirmishing or "small war" (la petite guerre as it was called in French, kleiner Krieg in German, or la guerrilla as it was known in Spanish) went on all winter (the Forage War was part of it). On the American side, the New Jersey militia had been invaluable for it, both because of their local knowledge and because at times they made up the bulk of the American army! At several points during the winter and spring, senior Continental officers gave thanks that the British seemed to have no impetus to probe harder, because they might have found nothing but a shell or framework of an opposing force. In March, Washington confided to a Congressman from Pennsylvania that he had barely 4,000 men under arms, while he believed the British had 10,000 (in fact, the British had closer to 15,000).

From Small War to War in Earnest

So what was the state of this American army, replenished and reinforced, ready to take on the British lion? In the next post, we'll look at the American forces in some detail, starting with the divisions of Anthony Wayne (who took over Lincoln's command after Bound Brook, when the latter was sent north to assist Major General Philip Schuyler defend New York State from Burgoyne's expedition) and of Nathanael Greene (whose division served as supports to Lincoln's Bound Brook outpost and which held the cream of the troops from the Commander in Chief's home state).

No comments:

Post a Comment