Apologies, faithful readers! Life has kept me busy with family matters and projects at work that have eaten up my time and energy. Weekend time to devote to work on Project 1777 has been sparse. I still mean to get a playing or two of some of these early skirmishes under my belt, both to re-familiarize myself and some of my comrades with the game system and to test out some of my ratings for the units involved.

Until I can make that happen, though, I have another battle synopsis to share with you. This engagement, though still a bit one-sided historically, could be touched up to make an interesting game a little more easily than Bound Brook.

|

| Nathanael Greene (Wikipedia) |

Back to 1777

When we last left General Sir William Howe, his ploy to draw the American Army into a trap at their forward post of Bound Brook had failed. Lt. Gen. Lord Cornwallis had surrounded and attacked the American post, chasing off Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln in his nightshirt (possibly even without that!) and capturing several cannon. But the Americans' nearest supports, Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene's division, had not arrived to reinforce Lincoln until after the British forces had left. Greene harassed the rearguard of the retreating British, then ensconced himself in Bound Brook.

However, after Greene had waited several weeks to see what else might develop, Lt. Gen. George Washington had pulled Greene's division back, leaving Bound Brook to lie in the debatable zone between the two armies. Bound Brook was too far from the main American position at Morristown to be supported adequately; it was too vulnerable to sudden attack to be a suitable forward base.

Nevertheless, Washington gave Howe some room to hope that the rebel commander could still be drawn out of his fastness in the Watchung Mountains. On May 28th, two days after Greene was recalled from Bound Brook, the American army moved from its winter camp at Morristown to Middlebrook, still in the mountains but closer to the British advanced base at (New) Brunswick.

A Cunning Plan...Foiled

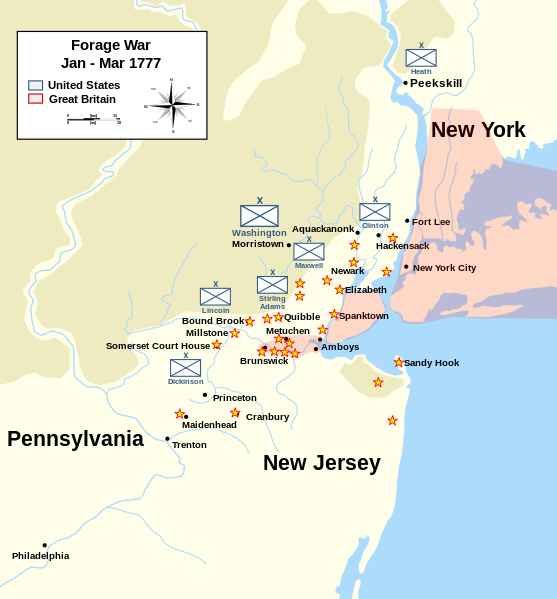

In June, Howe feinted, trying again to bring the Americans down out of the mountains and onto the plains of New Jersey where he hoped to defeat them in detail. Attempting to convince the Americans that he was marching toward the Delaware River and Philadelphia, the American capitol, Howe moved the main British army out of New York into New Jersey and settled for several days at Somerset Court House, south of Brunswick. But spies had told the Americans that the British bridging train, without which they could not cross the Delaware River, had remained in New York. Other supplies had also been left behind, meaning that the British could not stay in the field for long.Washington did not bite on Howe's proffered bait.

|

| William Alexander, Lord Stirling (Hidden New Jersey) |

Instead, Washington waited, and when Howe began moving back towards New York, the Americans came down from the mountains into the foothills, shadowing the King's army as it moved back to its base and picking off any stragglers who fell behind on the march. With his main army at the delightfully named Quibbletown, Washington sent an advanced guard under Maj. Gen. William Alexander to harass the British rearguard, much as Greene had chivvied Cornwallis's men after Bound Brook.

Alexander, sometimes known as Lord Stirling because he claimed to have inherited that Scottish title, had a reputation for bravery forged at the battle of Long Island the previous summer. Holding the right of the American line in that battle, Stirling had eventually been surrounded and his command forced to flee or surrender. His force had taken heavy losses, but through its sacrifice it had prevented the encirclement and capture of the entire American army. Alexander was later exchanged for Monfort Browne, the Governor of the Bahamas, who had been captured during an American raid on the islands in March of 1776. After returning to the army, Alexander commanded a brigade under Greene in the winter 1776/1777 campaign, leading the center of the American line at the battle of Trenton.

Now he sought to inflict some losses on the British rear guard as their army retreated to Perth Amboy, from there presumably to return to New York.

Barking at the Heels of the British Army

Howe determined to deal a sharp blow to Alexander's force and, as always, hoped that in the process he could draw the American field army into a decisive battle. Cornwallis, Howe's most aggressive general officer, received command of a strike force designed for speed and power. Cornwallis set off an hour after midnight with a task force of light dragoons, mounted and foot jaegers, the Queen's Rangers, a unit of Guards, and battalions of British and German grenadiers. Howe and Maj. Gen. John Vaughn followed with more jaegers, more British grenadiers, and a force of British light infantry.

|

| A Hessian officer's map of the battle of Short Hills (Wikipedia) |

As shown in the map drawn by Friedrich von Wangenheim, a Hessian mounted jaeger officer, Cornwallis' force and that under Howe advanced on parallel road, hunting for Alexander's division. Cornwallis made contact first, his jaegers coming into contact with American riflemen of Morgan's Corps just after dawn. The riflemen fought hard, not falling back until charged with the bayonet. As they were pressed, the riflemen fell back on Ottendorf's Corps, an independent light infantry force commanded by Lt. Col. Charles Armand Tuffin in the absence of its titular leader, and a body of New Jersey infantry--either militia or Continentals from Brig. Gen. William Maxwell's brigade--backed up by several artillery pieces. These supports helped stiffen the riflemen's resistance, but as more troops were deployed from the British column to the attack, the Americans were forced further back.

A Bitter Fight

|

| Charles Armand Tuffin, Marquis de la Rouerie (Wikipedia) |

Alexander had selected a defensive position on a ridge running perpendicular to the road. There he placed the main strength of his force, the remainder of Maxwell's brigade and a brigade of Pennsylvanians under Brig. Gen. Thomas Conway. Cornwallis tried to outflank this position by sending a battalion of Hessian grenadiers in a wide sweep around the Americans' left flank, but this was stalled by a battery of four French artillery pieces, carefully concealed in enfilade on a wooded hillside. One Guards officer foolishly attempted to capture the battery single-handed and was shot down at Alexander's direction. But a force of less than 2,000 men, even possessed of good defensive terrain, cannot hold against nearly 4,000 indefinitely. Eventually the pressure of the British attack forced Alexander's troops backwards, through the town of Westfield and over another line of wooded hills to the edge of the Watchung Mountains. The British, exhausted by nearly six solid hours of fighting, set to plundering Westfield. Joined by Howe's column, the expedition camped in area around the town that night and then marched back towards Staten Island the next day by way of Rahway.

Howe had again failed to draw out Washington's army, and he had missed even the prize of surrounding and capturing Alexander's division, though the British did take three of Alexander's four French guns back to New York with them. One amateur historian alleges that Washington heard the initial gunfire between the jaegers and Morgan's riflemen ten or fifteen miles away in Quibbletown and that the terrified commander immediately ordered his main army to begin fleeing back into the Newark Mountains.This seems unlikely, as does the claim that Alexander's fight at Short Hills was a brilliant strategic victory, allowing the main army time to escape a British trap. The trap had been set for Alexander, who did deftly avoid it, but Howe had not expected, when he set out in the dead of night, to encircle the American main army, only its somewhat dangerously advanced guard. One account even goes so far as to suggest that Alexander deliberately ignored an order from Washington to fall back from contact with the British main force; if that is true, Alexander was lucky to keep his command, escape or no.

A Tentative Order of Battle

My preliminary order of battle for this engagement (drawn from returns and assuming that Howe's column proves, as it did historically, to be too far away to support Cornwallis) looks something like this, much smaller than some of the fanciful and inflated numbers of some modern accounts. (Note: The larger number next to a unit is its historical strength, or my best approximation of it. The number in brackets is the number of stands used in the game to represent it: four-figure stands for infantry, two-figure stands for cavalry.)

Major General William Alexander, Lord Stirling (1,800 of all arms)

Lieutenant Colonel Charles Armand Tuffin

Ottendorf's Independent Corps (100 [2]): Line, Trained, Poor, Average

Morgan's Provisional Rifle Corps, detachment (100 [2]): Elite, Crack, Average, Excellent

Brigadier General William Maxwell

1st & 2nd New Jersey Continentals (300 [4]): Line, Trained, Average, Average

3rd & 4th New Jersey Continentals (300 [4]): Line, Trained, Average, Average

Spencer's Additional Continental Regiment (200 [3]): Line, Trained, Poor, Average

New Jersey state artillery (two sections of two four-pounders, 100): Line, Trained, Average, Average

Brigadier General Thomas Conway

3rd & 6th Pennsylvania Continentals (300 [4]): Line, Trained, Poor, Average

9th & 12th Pennsylvania Continentals (300 [4]): Line, Trained, Poor, Average

Pennsylvania state artillery (two sections of two four-pounders, 100) Line, Trained, Average, Average

Lieutenant General Charles, Lord Cornwallis (3,600 of all arms)

Captain James Weymss

Queen's Rangers (400 in two wings of [4] each): Line, Veteran, Average, Good

Ferguson's Rifle Corps (120 [2]): Line, Trained, Average, Excellent

16th Light Dragoons (300 in three squadrons of [1] each): Line, Veteran, Average, Poor

Royal Artillery (two sections of two six-pounder guns, 100): Elite, Veteran, Average, Good

Brigadier General Carl von Donop

Hesse-Kassel Feld Jaeger Korps, foot companies (100 [2]): Elite, Crack, Good, Excellent

Hesse-Kassel Feld Jaeger Korps, mounted company (80 [1]): Elite, Crack, Good, Excellent

Linsing Grenadier Battalion (430[5]): Elite, Veteran, Good, Poor

Minningerode Grenadier Battalion (430[5]): Elite, Veteran, Good, Poor

Lengerke Grenadier Battalion (440[5]): Elite, Veteran, Good, Poor

Hessian artillery (three sections of two four-pounder guns, 150): Line, Veteran, Average, Good

Lieutenant Colonel Sir George Osborn

1st Foot Guard Battalion (450 in two wings of [5]): Elite, Veteran, Good, Average

2nd Grenadier Battalion (500 in two wings of [5]): Elite, Crack, Good, Average

Royal Artillery (two sections of two three-pounder guns, 100): Elite, Veteran, Average, Good

.jpg)